The limit of Iran's industrial resilience

By Esfandyar Batmanghelidj

Editor’s introduction

In September 2022, the death of Mahsa Amini marked a major turning point for Iran. Her death sparked nationwide protests that rapidly evolved from calls to discard controversial hijab regulations to calls to overthrow the Islamic Republic. The Iranian government responded with repression, killing over 400 protesters in late 2022 and early 2023, according to human rights groups.

The Clingendael blog series ‘Iran in transition’ explores power dynamics in four critical dimensions that have shaped the country’s transformation since: state-society relations, intra-elite dynamics, the economy, and foreign relations. This blog post analyzes Iran’s manufacturing sector as key element of its ‘resistance economy’. It argues that the sector successfully adjusted itself to the sanction shocks of 2012 and 2018, maintaining economic stability, but is about to enter a period of long-term decline due to a lack of investment and modernization.

Iran’s manufacturing resilience

Over the last decade, Iran’s economy has successfully “resisted” sanctions in the sense of defying persistent predictions of impending economic collapse. Although Iran experienced sharp economic contractions after the imposition of financial and energy sanctions in both 2012 and 2018, the country’s manufacturing sector proved to be resilient.

While there has been much recent attention on Iran’s resurgent oil exports, over the last decade, the adaptation of the manufacturing sector has been the true source of Iran’s economic resilience under sanctions.

The fact that Iran’s manufacturing industry held up without turning inward has partly compensated for slower growth and lower exports in the energy sector due to sanctions constraints. This was achieved through a mix of supplier diversification and creating new export markets. For example, as part of their response to sanctions, Iranian manufacturing firms identified new suppliers for critical parts and machinery as European technological partners cut ties. Also, European parts and machinery were increasingly imported via third countries, such as Turkey and the United Arab Emirates. Finally, Iranian firms sought new technology providers, taking advantage of China’s emergence as a major exporter of manufactured goods around the same time that Iran faced greater economic isolation.

Finding new export markets proved more challenging, but Iran was able to grow the volume of non-oil exports to neighboring countries, particularly Iraq, the UAE, and Afghanistan. Iranian exporters were assisted by substantial currency devaluations that made their goods more competitive in regional markets. An increase in Iranian exports notwithstanding, banking restrictions and dysfunctional customs arrangements remained persistent headaches for Iranian firms and put limits on such growth. It is in part for these reasons that Iranian manufacturing firms cite negative prospects for export opportunities, as Javad Shamsi’s firm-level research shows.

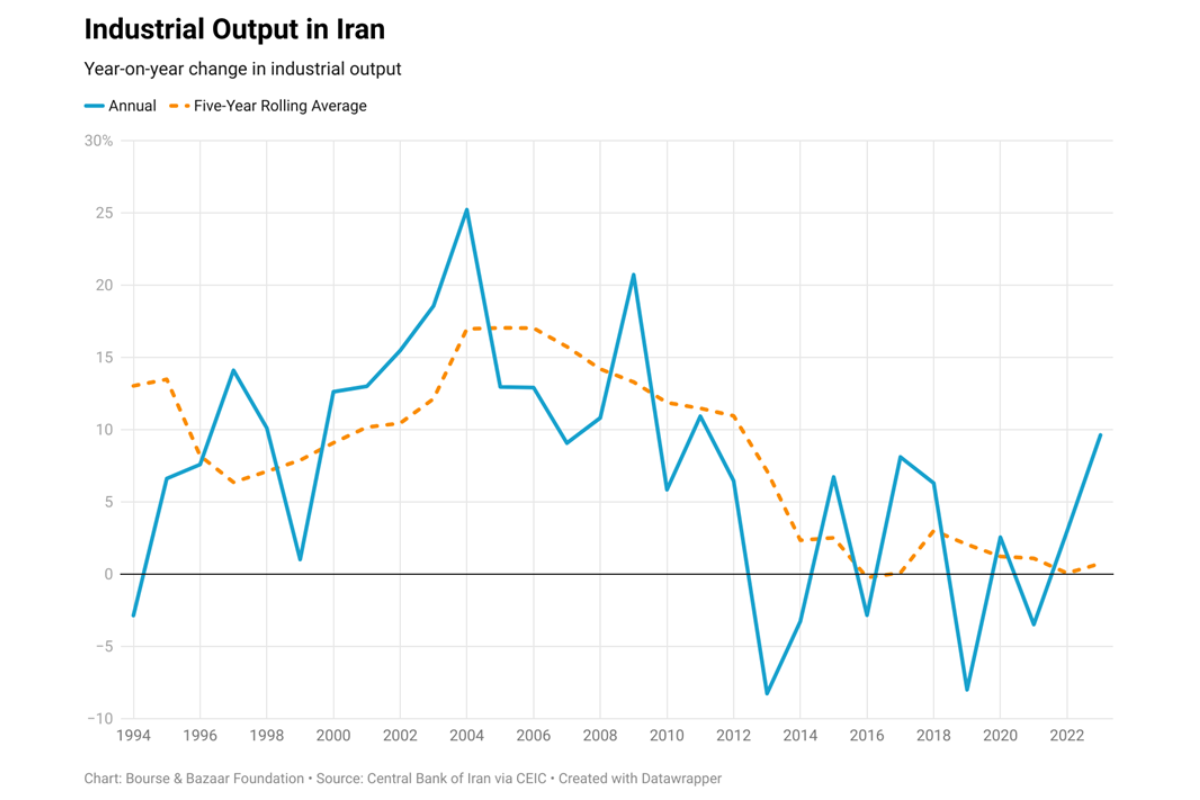

Despite regional trade being a rare bright spot for Iran’s manufacturing sector, the overall picture is one of stagnation and, as I will argue below, imminent decline. Largely due to the fact that sanctions brought an end to a 20-year period of foreign investment and technology transfer – an effect that is only felt in the medium- to long-term, Iran’s industrial production growth dropped from a year-on-year average of 13% between 2002 and 2012 to less than 1% between 2012 and 2022.

Even though stagnation equates with success for some Iranian policymakers — the fact that output has not declined is perceived to demonstrate that Iran’s economy has proven resilient in the face of trade disruptions, currency devaluation, and soaring inflation – they will not be able to cling to the narrative of the “resistance economy” forever. This is because sanctions have reduced investment as well as transfer of technological and managerial practices that Iranian manufacturing needs to stay on par with its industrial peers. In effect, the stability of Iran’s macro-economic manufacturing situation hides imminent decline. It is especially falling behind as manufacturing technology continues to develop and innovate across the globe. “Made in Iran” goods used to be of similar quality and sophistication as those produced in other developing economies, like Turkey or Brazil, but this is no longer the case.

But resilience is relative…

It is true that Iran’s factories continue to produce out trucks, cars, appliances, electronics, and a wide range of fast-moving consumer goods. But the manufacturing processes and industrial designs that underpin the production of these goods are often decades old. For example, the commercial vehicles division of Iran Khodro, the largest state automaker, still produces a short-bonnet Mercedes Benz truck designed more than 60 years ago. In 2017, following the implementation of the nuclear deal and related sanctions relief, Iran Khodro announced it would cease production of the short-bonnet truck as part of plans to produce state-of-the-art trucks under its joint venture with Daimler. But these plans fell through when President Trump withdrew from the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action in May 2018. Daimler announced it would exit its joint ventures in Iran just a few months later.

The issue can be summarized by saying that Iran’s economy remains productive, but increasingly produces goods that are inefficient, lack new features, and are more expensive than they should be. Economist Branko Milanovic has called this phenomenon “technologically regressive import substitution.” So long as their economies are sufficiently industrialized, countries affected by sanctions typically reduce their reliance on imported finished goods as part of their adjustment in the short- to medium-term. Sanctions interrupt imports of key inputs, but manufacturers are generally able to retool their supply chains and find new suppliers. Manufacturers also build up inventories of raw materials and parts to minimise disruptions to production. This allows domestic firms to continue to meet demand for most goods. Sanctions do gradually reduce purchasing power of households, but the effect on sales is moderated by the decrease in competition from imported goods and the fact domestic manufacturers tend to produce essential goods for which household demand is relatively inelastic. For this reason, market-leading firms can maintain or even grow their sales. There is even evidence that many firms in Iran have become more profitable under sanctions as they adjust to currency devaluation by passing higher input costs onto consumers while facing reduced price competition.

… as stagnation threatens to turn into decline

However, the outlook is less positive in the long-term, owing to a lagging effect of sanctions, namely a steep decline in investment. Gross fixed capital formation in Iran rose substantially from the mid-1990s until the imposition of major financial and energy sanctions on Iran in 2012. Total annual investment in Iran’s economy more than tripled in this period, which corresponded with the rapid expansion of Iran’s manufacturing base, particularly as European multinationals entered the Iranian market that brought new technology and production processes. In contrast, investment fell rapidly after 2012 when the sanctions shock tipped Iran’s economy into a recession. Last year, gross fixed capital formation was about half of the 2012 total, according to data from the World Bank. The sanctions relief of 2016 and 2017 did not lead to a bump in investment because the economic outlook remained uncertain. Eventually, sanctions returned.

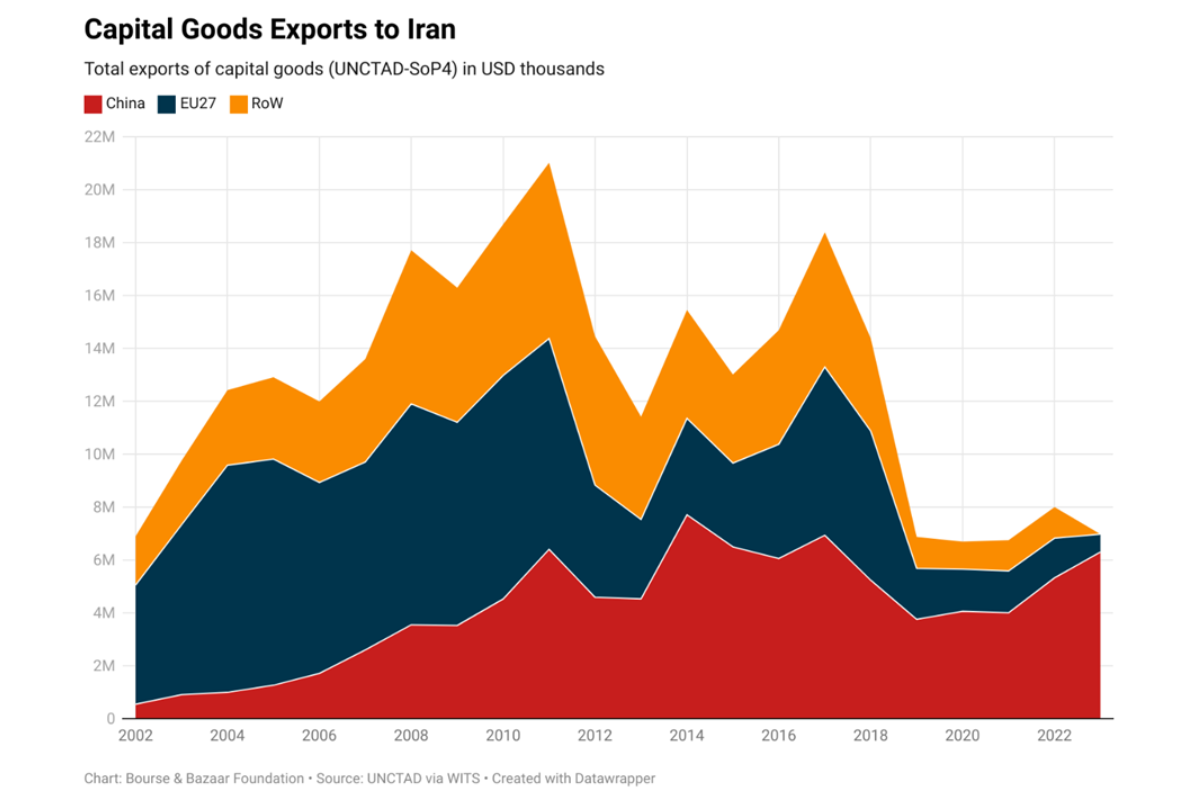

The lack of investment is clearly visible in trade data. According to data from the United Nations Comtrade database, Iranian imports of capital goods - a category that includes machinery and equipment used in production processes - totalled less than $8 billion in 2022. By comparison, capital goods imports amounted to more than $20 billion in 2011. These were the peak years of fixed capital formation in Iran. On the one hand, the reduction in capital goods imports reflects lower demand from Iranian firms. Firm owners are reluctant to invest given the uncertain economic environment and are more inclined to take profits out of their businesses rather than re-investing them. On the other hand, there are problems of supply. Many European producers of industrial equipment are unwilling to sell to Iranian customers given the risks associated with US secondary sanctions. Critically, Chinese suppliers appear similarly deterred. Chinese exports of capital goods to Iran rose from $4 billion in 2020 to $6 billion in 2023 corresponding to China’s post-pandemic push to boost its exports. But the 2023 total was at the same level as in 2017, the last year that Iran enjoyed sanctions relief. In other words, Iran has not been able to substitute the loss of its European industrial partnerships with Chinese ones.

Iranian officials appear aware of these problems. In a March 2022 op-ed, published in the Financial Times of all places, Iran’s finance minister, Ehsan Khandouzi called for “increasing government investment” and argued that the “public sector must play a more active role in investing in physical capital.” Khandouzi highlighted how “negative net investment in recent years” is “severely undermining future production and household welfare.” This kind of state-driven investment in the supply-side of the economy has much in common with the “military Keynesianism” that has underpinned the resilience of the Russian economy in the face of sanctions imposed following the invasion of Ukraine in February 2022. But even if Iranian officials understand the need to boost investment, including by use of the state’s fiscal capacity, they have yet to take action.

New vulnerabilities loom on the horizon

The lack of investment has left Iran’s manufacturing sector vulnerable to dramatic shifts in the global economy that are now underway. In particular, the resilience of Iranian firms will be tested by new competition from China. Faced with flagging domestic demand following the pandemic, Chinese policymakers have targeted higher exports in order to boost growth. The government has provided cheap loans and subsidies to increase manufacturing capacity with the result that Chinese exports to the Middle East have risen.

For example, Chinese exports to Iraq have surged, rising from $8 billion in 2018 to $14.5 billion last year. This included a tripling of Chinese steel export volumes after 2018 (when Iranian steel producers once more faced a sanctions shock). Those exports reached a value of nearly $1 billion in 2023. But Iraq also is the destination for around half of Iran’s steel exports, the value of which totals roughly $2.5 billion per year. Chinese exporters thus appear to be making inroads in Iraq as Iran’s largest steel export market. Iranian steel producers are concerned that further disruptions in Iran-Iraq banking ties could make it harder to stave off such Chinese competition.

Moreover, if Chinese exports to Iran itself keep increasing at the current pace, it could even lead to deindustrialisation. Such fears have delayed implementation of the Raisi administration’s 2022 move to lift curbs on the importation of cars, for instance. Prices for cars have soared in Iran as domestic production has lagged demand and opening the market to imports intends to reduce prices. But Iranian automotive manufacturers appear wary and some believe that removing the import restrictions could spell terminal decline for a sector that produces uncompetitive and expensive cars.

Unless there is a new wave of investment, Iran’s economic resilience will begin to falter. Deindustrialization would bring significant political consequences. In a recent speech, Masoud Nili, a key economic policymaker during the Rouhani administration, lamented the “gradual decline of Iran,” especially when compared to its neighbors. Ordinary Iranians increasingly experience their country’s decline and view claims of economic resilience as applicable only to the experiences of alienated elites. Meanwhile, President Raisi’s failure to implement “efficient economic management”—a campaign promise—has further delegitimised Iran’s political hardliners among Iranian voters, most of whom boycotted the recent parliamentary elections. From the early 1990s to the early 2000s, Iranian citizens experienced growing prosperity. They could be confident that standards of living would rise year after year. About a decade ago, this stopped being true as sanctions marked the start of a period of stagnation. Today, the economy is about to enter a period of relative decline.

Esfandyar Batmanghelidj is the CEO of the Bourse & Bazaar Foundation