Iran and Gaza in regional perspective: winning the battle, but losing the war?

By Hamidreza Azizi and Erwin van Veen

Editor's introduction

In September 2022, the death of Mahsa Amini marked a major turning point for Iran. Her death sparked nationwide protests that rapidly evolved from calls to discard controversial hijab regulations to calls to overthrow the Islamic Republic. The Iranian government responded with repression, killing over 400 protesters in late 2022 and early 2023, according to human rights groups.

The Clingendael blog series ‘Iran in transition’ explores power dynamics in four critical dimensions that have shaped the country’s transformation since: state-society relations, intra-elite dynamics, the economy, and foreign relations. This blog post analyzes the evolution of Iran’s security policy in the Middle East after 7 October. It argues that Tehran has successfully advanced potentially conflicting security objectives in the short-term, but also created new long-term risks – mostly economic - to the country’s political settlement.

To normalize or not to normalize is no longer the question

On 3 October, 2023, Ayatollah Sayyed Ali Khamenei, Iran’s Supreme Leader, warned Islamic governments against normalizing their relations with Israel, characterizing such efforts as “betting on a losing horse.” His pronouncement preceded the outbreak of war in Gaza that derailed the accelerating normalization between Saudi Arabia and Israel, as well as massively shifting public opinion in the Islamic world against Tel Aviv. Iran disavowed any involvement in orchestrating the 7 October attack. Various reports suggested Tehran was unaware of its specifics despite its longstanding support for Hamas. Nevertheless, Iranian leaders have eagerly tried to take credit for the blow inflicted on Israel. Khamenei’s followers view the impact of the conflict on the Islamic world as validating their longstanding anti-Zionist and anti-US discourse, as well as their investment in the axis of resistance – Hamas included.

As the Israeli military campaign in Gaza unfolds, Tehran has pursued three regional security objectives more or less in tandem. First, maintaining deterrence against a potential direct US/Israeli attack. Second, increasing the cost of the Israeli military campaign in Gaza to the US and Israel while avoiding a regional high intensity conflict. Third, upholding the coherence of the axis of resistance in the face of US and Israeli reprisals. Below, we dissect how Tehran has performed on these objectives, and what longer-term risks for Iran have emerged in the process.

Achievements of Iran’s regional security policy since 7 October

Substantial US military assets were deployed to the Middle East within two weeks of 7 October: Two aircraft carrier battle groups, an amphibious marine rapid response force, air defense batteries and fighter aircrafts. Their stated purpose was to prevent Iran from exploiting Israeli weakness, but many of these capabilities could also have enabled a US/Israeli strike against Iran once the initial shock of 7 October had been absorbed. A key Iranian objective has been to deter any such US/Israeli attack.

Tehran’s main line of deterrence has been discursive. In his first public reaction to 7 October, Supreme Leader Khamenei fully endorsed the violence of what he termed the “courageous Palestinian youth.” His rhetoric conveyed robust support and carefully portrayed the attack as a wholly Palestinian initiative, absolving Iran of any direct involvement. It has been a recurrent sleight of hand by Iranian officials ever since to frame the attack as a manifestation of Palestinian resolve and as a response to Israel’s decades-long occupation. While it is clear to most observers that Hamas benefited from long-term Iranian support in creating the capabilities that made the 7 October attack possible, no government actor has credibly suggested direct Iranian involvement.

Next to its public discourse, Tehran’s deterrence has been diplomatic in nature. Senior government leaders embarked on an intensive diplomatic campaign across the Middle East in short order, which has sought to leverage the growing negative sentiment towards Israel to strengthen Iran’s own ties with Arab states, most notably by deepening diplomatic engagement with Saudi Arabia, but also by seeking rapprochement with Egypt. Just as the US Secretary of State Blinken toured the region to seek support for the US position behind Israel, so did Iran’s foreign minister Amir-Abdollahian engage in several regional tours of “resistance diplomacy” to solicit support for Tehran’s position against Israel. His meetings with state officials and leaders of Iran-backed groups during these tours furthermore sought to ensure a common stance by the axis of resistance against the US and Israel.

Iran has been quite successful in marshalling Arab support to its side by some measures, but not by others. The increased risk of American – Iranian high intensity conflict across the region has accelerated the rapprochement between the Gulf states and Iran, especially Saudi Arabia, who are keen to avoid getting caught in the middle. The restrictions on US military use of Emirati airspace, as well as the meeting between Iran’s President Raisi and the Saudi Crown-prince bin Salman at the margins of an emergency summit of the Organization of Islamic Cooperation offer two examples. In contrast, none of the Arab countries in the region has followed Iran’s call for sanctions against Israel and neither has Saudi (or Gulf) investment in Iran materialized yet.

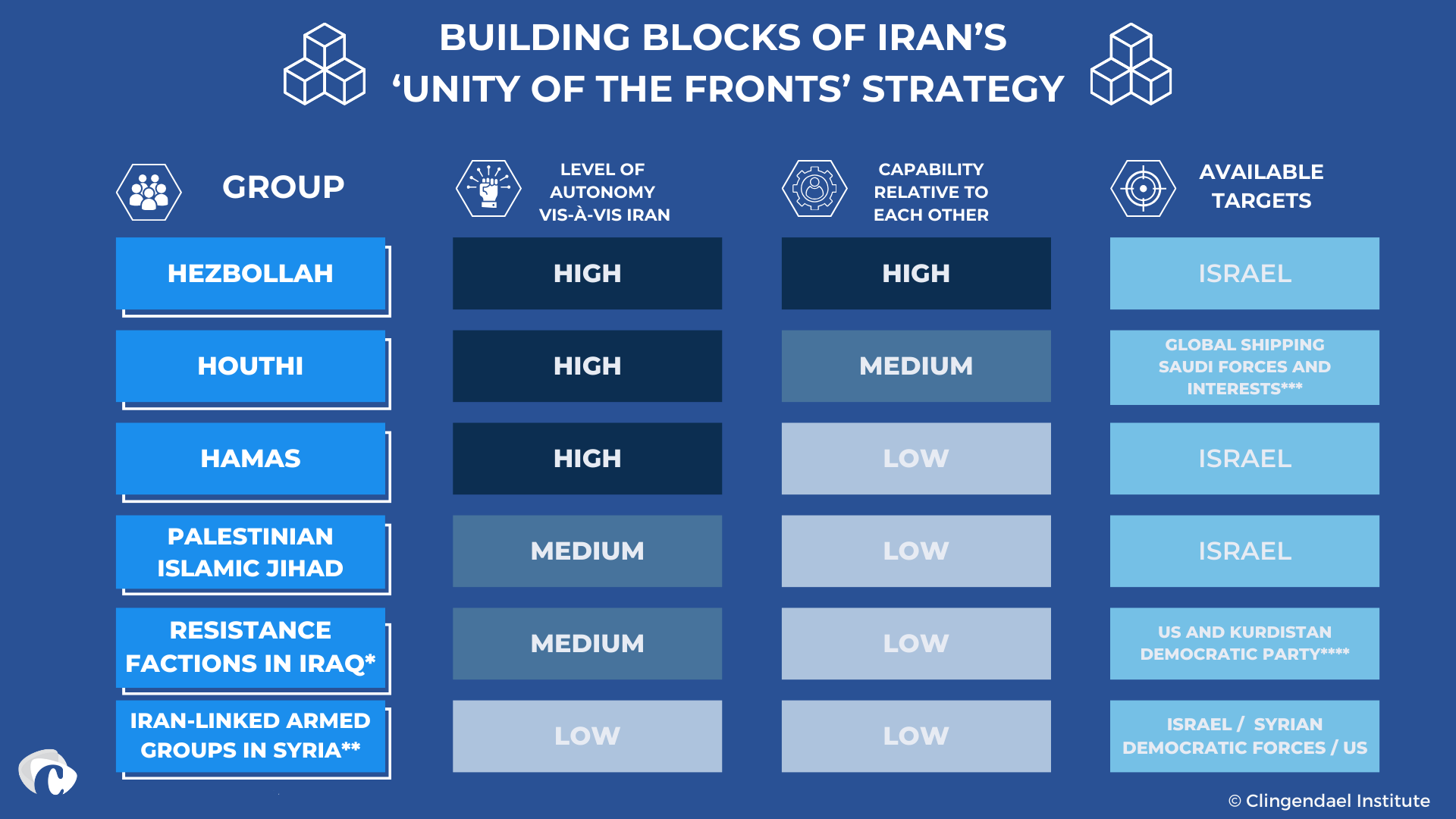

As a second objective, Iran has sought to raise the cost of the Israeli military campaign in Gaza to both the US and Israel while avoiding high intensity regional conflict. This job has mainly fallen to Hezbollah and the Houthis (see Figure 1 below). Hezbollah’s presence and actions on Israel’s northern border ties down thousands of Israeli soldiers and prevents the return to their homes of over 95,000 Israeli IDPs. Meanwhile, the Houthis have caused major shipping companies to reroute maritime traffic via Cape of Good Hope, raised shipping insurance cost in excess of 1% of a ship’s value for just seven days of sailing and caused Egypt’s Suez Channel revenues to fall by about USD 3-4 billion to date. Israeli responses in Lebanon have remained contained to avoid a two-front war while the main US response took the form of the naval Operation Prosperity Guardian in the Red Sea. In other words, Iran uses two different theaters to raise the cost of conflict with actions in each theater remaining contained to it, at least for the time being.

A third Iranian objective has been to maintain coherence among axis of resistance members to the point that enables continued coordinated action in the face of US and Israeli reprisals. This “unity of the fronts strategy“, as Iran calls it, refers to the axis dispersing US and Israel’s diplomatic and military capabilities by acting simultaneously yet asymmetrically on multiple fronts in line with the capabilities of, and targets available to, different axis members (see Figure 1 below).

From the perspective of Iran’s “Unity of the fronts” strategy, 7 October was a godsend. Frequent Israeli strikes on Iranian positions in Syria, military and nuclear facilities inside Iran as well as assassinations of Iranian nuclear scientists – all as part of the “shadow war” between both countries – had been fueling speculation about Iranian strategic weakness. The Hamas attack offered Tehran an opportunity to showcase Israeli weakness in turn, claim a share of a “victory” and thus counter perceptions of Iranian vulnerability.

Moreover, the swift mobilization of a number of axis of resistance groups in support of Hamas – each in their own manner and with the sum of its parts being less than what Hamas had expected – also underscored the efficacy of Iranian regional strategy. It vindicated Tehran’s long-term investment in the axis as instrument of coercive diplomacy next to demonstrating a functional division of labor between axis members. The past few months have also made clear, however, that the axis is not a suitable tool for direct military confrontation in the conventional sense, notably because its lack of air defense capabilities.

In brief, Iran has so far successfully utilized the Israeli military campaign in Gaza as a platform to demonstrate the strategic relevance of the axis of resistance in terms of its coherence and ability to impose cost on adversaries. It also used the events after 7 October to augment its discursive and diplomatic influence in the Middle East for the purpose of deterrence, albeit to more mixed effects.

Challenges to Iran’s foreign policy orientation after 7 October

President Biden has sought to revive the nuclear deal with Iran since 2021, but efforts have been marred by delays and miscalculations on both sides. This led to a diplomatic standstill by mid-2022. In an attempt to create new momentum, an “unwritten understanding” was reached in the summer of 2023: the U.S. agreed to unfreeze $6 billion of Iranian assets and ease some sanctions while Iran pledged to halt the expansion of its nuclear program and to reduce tensions in Iraq and Syria in exchange. The events on and after 7 October relegated this agreement to the junkyard. US Congress tried to block the funds and indirect diplomatic dialogue between Iran and the US came to a halt. It has become much less likely that a path can be charted that balances non-proliferation with Iran’s re-integration into the global economy. Negative views of Iran in the West have hardened instead, rightly or wrongly, given Tehran’s support for Hamas and the potent demonstration it has given of the axis of resistance in action. Especially the cost that the Houthis impose on global shipping and trade have been significant.

In consequence, the US has passed several pieces of legislation to tighten sanctions on Iran’s oil trade, including the “Stop Harboring Iranian Petroleum” bill that targets ports and refineries dealing with Iranian oil. Amos Hochstein, Biden’s energy security advisor, also announced more stringent enforcement of existing US sanctions. On top of this comes Iraq’s decision to revoke the license of the National Bank of Iran and restrictions on several Iraqi banks to use U.S. dollars. Given US influence on Iraq’s banking system, these moves aim to block Iranian access to US dollar. Whether all these measures will produce strategic results remains to be seen – Iran’s economy faces major constraints due to sanctions and its lack of global integration, but is nevertheless projected to soldier on in 2024 - they do indicate that greater (economic) confrontation lies ahead. Western hostility might deepen if Iran actually provides Russia with short- and medium-range missiles, as has been mooted recently.

Restrictive economic measures, reduced contact with Washington, an enhanced US military presence in the Middle East and the threat of an Israeli offensive against Hezbollah might even push Iran to take the final steps in its development of a nuclear deterrent. This could, in turn, expose the country to higher levels of sabotage, assassinations and even direct strikes. This scenario amounts to exactly the type of high intensity regional conflict that Iran has so far sought to avoid.

Direct strikes could also come about by chance escalation. For example, Kata’ib Hezbollah, an Iran-backed Iraqi armed group, attacked a U.S. base on the Jordan-Syria border in late January and killed three American soldiers. This prompted calls within the U.S., particularly from Republicans, for direct military retaliation against Iran. President Biden opted instead for a limited counter-response in eastern Syria and Iraq, as well as a cyber-attack against an Iranian vessel linked to the Houthis – but the risk of (further) escalation was there.

Although Iran’s overall diplomatic and security position in the Middle East has arguably improved in the direct aftermath of 7 October, the same cannot be said for relations with its direct neighbors Iraq and Pakistan. Missile strikes on both countries intended to emphasize Iran’s an eye for an eye policy, but sparked serious tensions instead.

To begin with, a missile attack by the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) on Erbil in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq was widely perceived, including in Baghdad, as a flagrant violation of Iraq’s sovereignty. Iran claimed to target a Mossad base in the city, but failed to offer credible evidence of the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP) facilitating Mossad operations, let alone an intelligence base even though it maintains good relations with Israel. The episode negatively affected the delicate balance of bilateral relations.

The strike in Pakistan purportedly revenged the death of eleven Iranian border guards at the hands of Jaish al-Adl, a Balochi separatist group, a few weeks earlier. Yet, Pakistani public and elite opinion have generally been favorable of Iran while Pakistan’s conventional forces are estimated to be much stronger. The IRGC’s failure to coordinate its strike with the Pakistani army triggered a swift response. It took the form of missile and drone strikes against the Balochistan Liberation Army, another Balochi separatist group but this time one operating in Pakistan from bases in Iran and Afghanistan.

In brief, in addition to noted successes, Iran’s actions after 7 October also ended nuclear diplomacy, increased tensions with the West, increased economic pressure on Iran and created new ruptures with friendly neighbors Iraq and Pakistan.

The net balance of 7 October to Iran so far

Tehran views enhanced coordination within the axis of resistance and the damage it has inflicted on the US, Israel and the West as significant triumphs. Iran has also made progress in expanding its diplomatic clout in the Middle East through a series of high-level meetings with Arab officials and leaders. Yet, although relations are improving, deep mistrust remains and GCC financial flows to Iran have yet to materialize.

In contrast, Iran’s long-term strategic position has arguably deteriorated. This is due to the termination of nuclear negotiations, the threat of tighter enforcement of US sanctions and deteriorating relations with friendly neighbors. The economic impact of such developments would be compounded by the financial cost of an escalating Gaza conflict. In this scenario, the IMF projects GDP contractions of up to 5% for Iran, 20% for Lebanon and 8% for Yemen.

One can argue that 7 October and its aftermath have enabled Iran to realize substantial gains in the security dimension of its regional policy. At the same time, Iran’s actions have also created strategic longer-term risks. A major issue is that the socio-economic prospects for many Iranians will worsen as a result of greater sanction enforcement by the US and an absence of nuclear diplomacy. While this appears manageable from a protest perspective for now, more decisive tipping points for Iran’s governability could be reached quickly if a regional high intensity conflict breaks out. After all, as earlier blogs have pointed out, the Islamic Republic has increasingly shaky socio-economic and corroded political foundations.