Fifty shades of hardliners: Intra-elite dynamics in Iran

By Hamidreza Azizi and Erwin van Veen

In our introductory blog, we identified intra-elite dynamics as a key driver of Iran’s ongoing transition, in addition to three others: state-society relations, economic prospects and foreign relations. This blog examines how relations among Iran’s political elites have evolved in the social, economic and foreign policy areas. The blog also discusses implications of shifts in elite relations for the broader process of transition in Iran.

Introduction

During the 2022-2023 “woman, life, freedom,” protests, rumors about rifts among Iran’s political elites regarding the appropriate governmental response gradually grew louder. A notable example was Khamenei's alleged encouragement of the police force to repress protests more harshly when some other senior leaders would counsel restraint. Given the opaque nature of Iran’s political system and the complex relationships between its elites at various levels of power, reports about elite infighting should be approached with a degree of caution. Even so, shifts in elite relationships were visible before protests erupted.

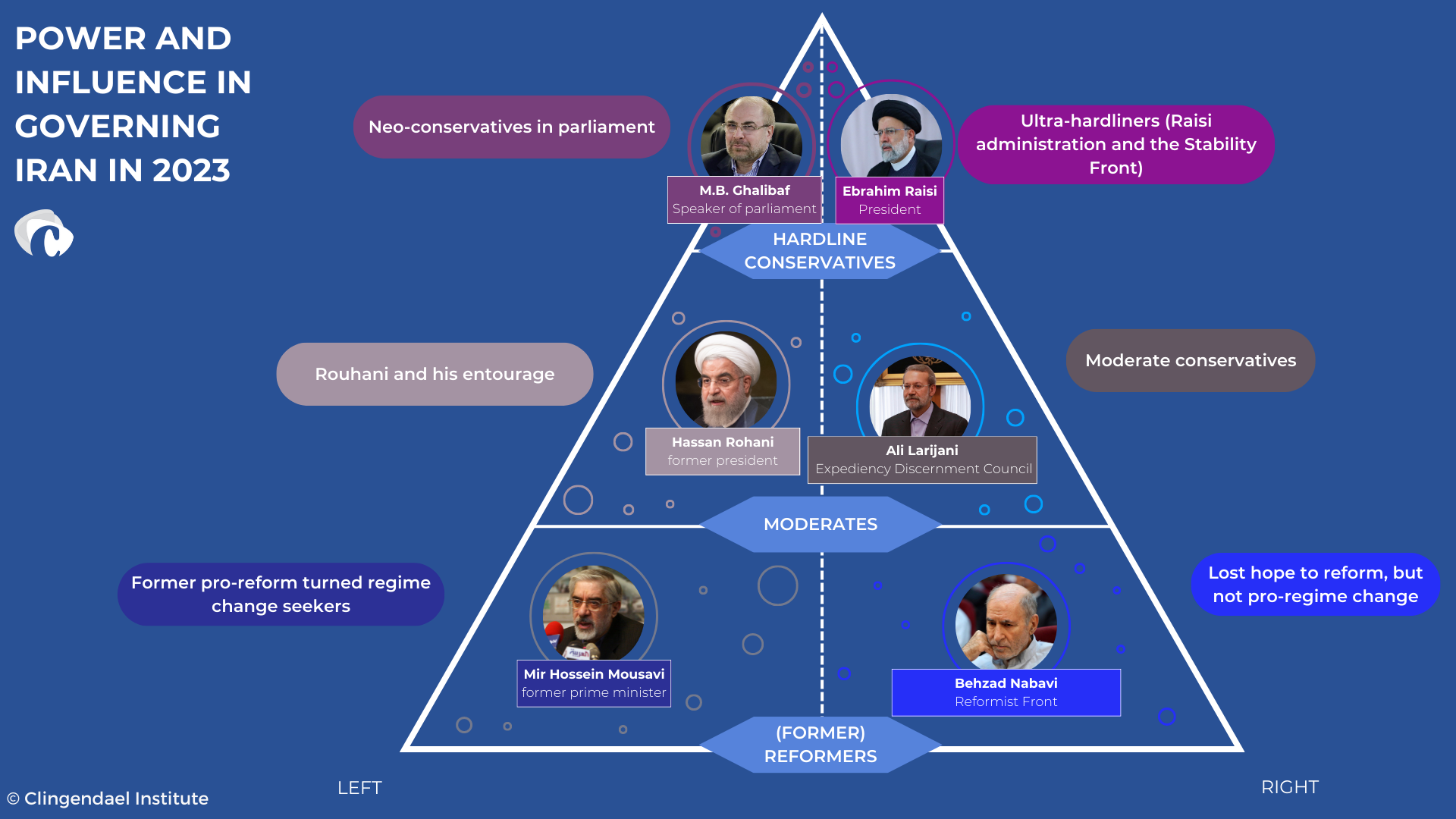

The 2021 Iranian parliamentary elections heralded a decisive turn towards hardline factions gaining dominance in the governance of Iran, despite the fact that public disillusionment ran high and voter turnout reached only 42,57%. The presidential elections of the same year confirmed hardline ascendency by installing the conservative hardliner Ebrahim Raisi as President by means of a rigged procedure. Before 2021, Iran’s conservative and hardline elite factions already exercised substantial influence behind the façade of a more moderate and pro-reform administration however, to the point of enjoying a de facto veto. After 2021, hardline and conservative factions have been unequivocally in charge. But their domination of parliament and the presidency did not bring political stability about, as some have suggested it would. Instead, reformist elite factions were demoted and competition increased between hardline elite factions themselves.

Elites and state-society relations

The 2022/2023 protests caused a further deterioration of state-society relations – here understood as the tension between the discourse and reality of popular protests versus counter-claims by state representatives - that translated into shifts in relations between the country’s political elites. Protests broadened the gap between hardline elite factions currently in charge and reformist elite factions demoted in 2021. They also sparked discord between ruling elite factions themselves. Beginning with the former, several demoted reformist elite factions that ran government in Iran under presidents Rafsanjani (1989-1997), Khatami (1997-2005) and Rouhani (2013-2021) started to advocate for a transition beyond the current governance structures of the Islamic Republic. Mir-Hossein Mousavi, a former Prime Minister turned opposition figure since 2009 and under house arrest since 2011, publicly argued for constitutional and systemic reform. Mostafa Tajzadeh, a former Deputy Minister of Interior and reformist leader presently in prison, echoed these sentiments. Former President Mohammad Khatami underlined the futility of attempting reforms within the existing constitutional and moral framework of the Islamic Republic, even though he stopped short of suggesting regime change.

In contrast, moderate ‘in-between’ elite factions, personified by ex-President Hassan Rouhani, remained conspicuously silent during the protests. However, as street demonstrations tapered off, Rouhani and his allies began critiquing the government’s socioeconomic policies. Unlike the reformists, this group retains ties with hardline elite factions and seeks to leverage public protests as a means to orchestrate their political comeback. Their focus is on the upcoming parliamentary elections of March 2024.

In parallel, ruling hardline elite factions exhibited discord among themselves during the recent protests, particularly over the government’s handling of the hijab issue. The judiciary proposed to tighten enforcement and punish non-compliance more harshly while the Raisi administration initially prepared a bill that claimed to be based on a softer ‘cultural approach’, rather than criminalization (it was rescinded after backlash). It was in the same vein that a cohort of veteran military commanders convened to discuss essential reforms within the Islamic Republic, but did not manage to convince the country’s top leadership of their views. Finally, several hardline parliamentarians voiced concerns over the securitization of political appointments and the dominance of a security-oriented mindset. Parliament member Jalil Rahimi Jahanabadi criticized Raisi for entrusting key civilian and foreign policy responsibilities to military figures, lamenting that “The country has become like a barracks.”

In brief, relations between Iran’s 'reformist', 'moderate’ and ‘hardline’ elite factions have become tenser in function of their respective positioning towards the protests. This shift indicates that public opinion on social issues shapes elite factional views and responses more than the opposite. It also highlights divisions within each set of elites on social issues.

Elites and the economic situation

Iran’s precarious economic situation and its bleak prospects have produced intense disagreement among representatives of ruling elite factions in parliament, President Raisi’s administration and the cabinet about the appropriate governmental response. Compared with habitual turnover rates, personnel changes in the administration’s key economic positions have come fast and furious since Raisi took office. They are an indicator of serious disagreement. By June 2022, Raisi had replaced his Minister of Cooperatives, Labor, and Social Welfare. By October 2022, Rostam Qassemi, the Minister of Roads and Urban Development, had stepped down. In December 2022, a new Central Bank Governor had been installed, and by March 2023, both the Head of the Planning and Budget Organization and the Minister of Agriculture had been dismissed. In a span of twenty months, three ministers resigned, a minister and a deputy were removed by presidential decree, and one minister was impeached by parliament (the Minister of Industry, Mining, and Trade in April 2023).

The poor economic situation and failing economic policies have also sparked disagreements within Raisi’s cabinet. Reports suggest there is a severe rift between Mohammad Mokhber, the First Vice President, and Mohsen Rezaei, the former Vice President for Economic Affairs. It culminated in Rezaei’s resignation in May 2023. The struggling economy has furthermore stirred discontent within military ranks. The Quds Force of the IRGC is increasingly becoming an object of envy among other parts of the security forces due to its special budget, better facilities and higher salaries. In turn, this has raised concerns among some commanders about erosion of the coherence of the security forces.

This tumult underscores the pressure on the Raisi administration to improve its handling of Iran’s economic crisis (see blog #3 of ‘Iran in transition’). As the 2024 elections loom, parliamentarians representing economically disadvantaged areas are ramping up their criticism of the administration in a bid to secure re-election and expand their influence. Unsurprisingly, demoted reformist and second-tier moderate elites are trying to use the economic situation to stage a comeback as well. For example, Eshaq Jahangiri, former First Vice President under Rouhani, and Abdolnaser Hemmati, the former Governor of the Central Bank, have become vocal critics of Raisi’s economic policy. Such is the severity of the economic crisis that even Supreme Leader Khamenei noted that “If we have four or five critical weak points in our country, the economy is at the top of all of them.”

In brief, the economic situation provides fertile ground for tensions between reformist, moderate and hardline elite factions, as well as between hardline factions themselves. As a result, economic policy will become increasingly important to leverage popular discontent and compete politically within the Raisi administration in the run-up to the 2024 parliamentary elections.

Elites and the foreign relations

Since the start of Raisi’s presidency, foreign relations have been a major area of discord between reformist and hardline elite factions. Even before his tenure, Raisi and his network critiqued the foreign policy of former president Rouhani and his Foreign Minister Mohammad Javad Zarif, accusing them of selling Iran out to the West on the nuclear issue. They argued the US could be coerced into rejoining the JCPOA on Iran’s terms, including assurances and compensation.

However, two years into his term, the Raisi administration has not only failed to revive the JCPOA, but it has also presided over surging tensions with the West. Of late, the course of the nuclear negotiations has fueled divisions among ruling hardline elite factions as well. Pro-reform news website Entekhab detailed how ultra-hardliners, especially the “Front of Islamic Revolution Stability” (or the “Stability Front,” as it’s often referred to – a radical political faction deeply influenced by the ideology of the late hardline cleric Ayatollah Mohammad-Taqi Mesbah Yazdi), obstructed the revival of the nuclear agreement against the wishes of the Raisi administration – even though it is also ‘hardline. For example, when Iran and the West were on the brink of reviving the JCPOA in the summer of 2022, Stability Front members proposed delaying the agreement by asserting that Europe’s impending “harsh winter” – due to the Ukraine conflict and the shortage in Russian gas supply to Europe – would force the West to accept Iran’s terms. In March 2022, a member of parliament affiliated with the Stability Front leaked details of a potential agreement between Iran and the West, claiming it was not favorable to Iran. Naturally, this move damaged the draft’s prospects substantially. Note that the Stability Front has representatives in both the parliament and Raisi’s cabinet. For example, Saeed Jalili, a former secretary of Iran’s Supreme National Security Council (SNSC) and chief nuclear negotiator during Mahmoud Ahmadinejad’s presidency, is linked with the Front. It was Jalili who allegedly advocated to increase uranium enrichment to 90 percent (ultimately rejected by the Supreme Leader).

In brief, the consolidation of control in the hands of hardline factions since 2021 over Iran’s foreign policy has neither produced a consensus that can enable a breakthrough in the nuclear negotiations, nor has it generated a foreign policy that is more coherent as a whole. It did, however, produce a shift of diplomacy and trade towards ‘the East’, as well as greater confrontation with the West (see blog #2 of ‘Iran in transition’).

Broader context: Transitioning to the post-Khamenei era

Zooming out, all current power dynamics and factional strife in Iran must be considered in view of the impending transition to the post-Khamenei era. Most elite factions – reformist, moderate and hardline alike – are maneuvering to secure their position in the power hierarchy with a view to the inevitable death of Ayatollah Khamenei (he is 84 at present). Their objectives extend beyond the selection of a new leader and include making changes to Iran’s political system. This situation makes the 2024 parliamentary elections in Iran significant. Some elite factions, like those around Hassan Rouhani and Ali Larijani, the moderate and conservative former Speaker of Parliament, are eyeing the elections as an opportunity. By winning seats back compared with 2021, they hope to bolster their power base and influence the succession process that is expected to unfold over the next four years.

However, such ambitions will likely hit the wall called the Guardian Council, the body that vets candidates for their ideological conformity to the principles of the Islamic Republic. It is widely expected that it will once more disqualify all candidates that deviate from prevailing dogma and policy. Additionally, Iranian voters are hardly motivated to turn out to vote, which facilitates hardline elite factions to retain control of parliament. Violent suppression of protests, increasing restrictions on political and civil liberties, and worsening economic conditions all play their part. The paradox of repression and mismanagement helpfully reducing voter turnout will not be lost on Iran’s ruling elites.

Simultaneously, competition among hardline factions is increasing as they seek to consolidate their own control within the existing power structure. The Stability Front has successfully positioned itself at key centers of power, thus strengthening its influence when Khamenei passes away. Yet, its expansion has met both with criticism and resistance from other hardline and conservative factions, some of which are also represented in the parliament. None of these internal conflicts among hardline factions signal fundamental controversy about the principles of the Islamic Republic or its ideological foundations, however. Instead, they represent a struggle for relative power. As Ali Afshari, a political analyst, elucidates, “Political developments in the context of absolute power in the Islamic Republic indicate the permanence of the process of divergence and the continuous removal of a portion of the ruling elites...In fact, [in the Islamic Republic] the ruling power has always been divided into two” [i.e. never ending factional strife].

In conclusion, intra-elite relations are fluid at the surface and plenty of change seems afoot. Below the surface, reformist factions have been demoted and relegated to the sidelines of Iran’s political arrangements while hardline factions remain both in control and united in their deeper views of the Islamic Republic. Progressive change will remain a scarce commodity in the near future. The next blog in our series ‘Iran in transition’ will appear towards the end of September after what we hope will be a good summer break for many of you.

The next blog in our series ‘Iran in transition’ will appear towards the end of September after what we hope will be a good summer break for many of you.