Sending migrants back to Libya? Possibly counterproductive

As the holder of the EU presidency, Malta aims to send migrants intercepted by European rescue ships back to Libya. That requires an agreement with the Libyan government, along the lines of the deal with Turkey whereby Ankara received money and political promises in exchange for receiving migrants. But Libya is not Turkey. Handing migrants over to the Libyan government is dangerous and will not help the fight against human smuggling and migration to Europe.

After the ‘success’ of the EU-Turkey deal – which resulted in a sharp drop in the number of refugees and migrants trying to reach Europe from Turkey but also led to large numbers of people being imprisoned in Greece – the EU has now turned its sights on Libya with a view to setting up a similar agreement. These plans show just how powerless the European countries are when it comes to the necessary internal reforms of their own asylum system. Instead of putting their house in order, this latest plan can best be likened to a quick prayer devoid of any vision or sense of reality. Libya is not Turkey, and the assumption that cooperation with the internationally recognised government of Libya, the Government of National Accord (GNA), is an effective solution to combat human smuggling and curb the number of migrants making the crossing is a gross misconception.

In the first place this is because the GNA, which has been based in the Libyan capital Tripoli since March 2016, neither has effective control of large swathes of the country nor enjoys the trust of the main domestic political players. Actual power in Libya resides with the countless militias that are waging an internal armed conflict. Some of those militias have sided with General Khalifa Haftar in the east of the country, supporting a shadow government that reportedly enjoys more support than the GNA. The weakness of the GNA is illustrated, for example, by the fact that the government kept its arrival in Tripoli secret due to fears of violence and the fact that in all those months since taking office, GNA prime minister Serraj has been unable to travel outside of the capital due to security concerns. Being the straw puppet that it is, the GNA will not be able to link any genuine threat or consequences to the activities of the human smugglers.

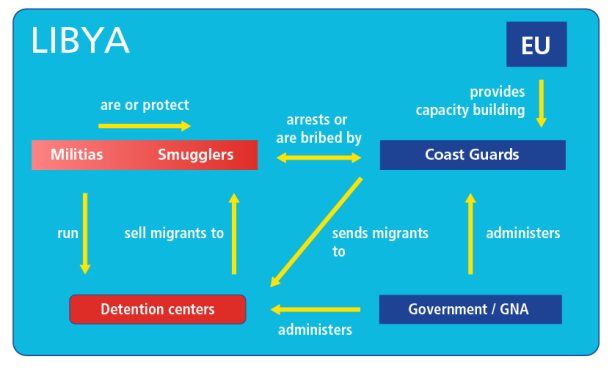

Second, politics in Libya is heavily militarised: the GNA relies on powerful militias for protection and calls on them to enforce public order on behalf of the state. This also applies to the detention centres, where migrants who either resided illegally in Libya or who were intercepted in Libya’s territorial waters are detained. Amnesty International and Doctors Without Borders have already reported that there are few places in the world where people are held in such abominable conditions as these detention centres, often empty warehouses with no facilities. Our investigations also show that militias guarding the detention centres on behalf of the GNA often collaborate with human smugglers; smugglers are buying detainees from the guards in order to force them (back) onto boats to Europe. A vicious circle looms.

Third, the profits for the armed groups involved in ‘managing’ migrants are often twofold. In the first place migrants are an important source of income. They leave a detention centre only when their family buys their freedom, when they themselves have been able to cough up the required money through forced labour, when a smuggler buys them out or when they die. The coast guard also takes a slice of the profits by granting migrants and smugglers free passage in exchange for payment. The current EU plan maintains the criminalisation of migrants staying in Libya – and thereby contributes to this business model. The criminalisation of migrants also strengthens the militias’ grip on power, since their help is required in guarding the detention centres. Perpetuating these militias does nothing to resolve the internal conflict that has gripped Libya for years and that serves as a strong push factor driving migrants who were never intending to come to Europe into the sea.

European leaders must realise two things: first, the GNA is not a neutral player in the migration issue – there are hardly any neutral players in Libya. Cooperation with one of the Libyan governments outside an internal peace process may only extend the internal conflict and thus push even more migrants out of Libya. Second, the proposed plan does nothing to thwart the human smugglers. They operate with the knowledge (and cooperation) of the authorities and local militias. Migrants in Libya are a commodity. Sending them back will not destroy the smugglers’ business model; it will only add to the migrants’ misery. Unless a comprehensive plan is devised for the humane reception of migrants in and out of Libya, every migrant who sets foot in the country will run a serious risk of exploitation, torture, rape and death.

This opinion piece is based on the yet to be published report entitled ‘Only God can stop the smugglers. Understanding human smuggling networks in Libya’ (the Clingendael Institute, January 2017) and appeared in the Dutch daily De Volkskrant on 17 January 2017.