Iranian reactions to 7/10 and the invasion of Gaza

By Hamidreza Azizi and Erwin van Veen

Introduction

In September 2022, the death of Mahsa (Jina) Amini marked a major turning point for Iran. Her death sparked nationwide protests that rapidly evolved from calls to discard controversial hijab regulations to calls for the overthrow of the Islamic Republic. The Iranian government responded with repression, killing over 400 protesters in the course of late 2022 and early 2023, according to human rights groups.

The Clingendael blog series ‘Iran in transition explores power dynamics in four critical dimensions that have shaped the country’s direction since: state-society relations, intra-elite dynamics, the economy, and foreign relations. This blog post analyzes what the respective reactions of Iran’s political elites and its population to 7/10 and the invasion of Gaza tell us about intra-elite dynamics and state-society relations in the country.’

The official versus the public response to 7/10 and the invasion of Gaza

Since its establishment in 1979, the Islamic Republic in Iran has consistently championed Palestinian movements against Israel. This stance is rooted in its ideological orientation embedded in the Iranian reading of political Islam, inspired by Shiism, that calls for fighting against oppression and standing up for the oppressed across the Islamic world. Consider, for instance, Iran’s constitutional principle of providing ‘support for the oppressed’. To Tehran, support for Palestine and opposition to Israel regarding occupation is not a matter of policy, but part of the identity of the Islamic Republic. But it is worth noting that Iranian links to Palestine date back to the period before the Islamic revolution when opposition groups to the Shah’s regime established ties with the Palestinian Liberation Organization (PLO). Some Iranian dissidents received training in guerrilla warfare from the PLO to support their fight against the Shah’s military and security apparatus, and went on to rule Iran after the 1979 revolution.

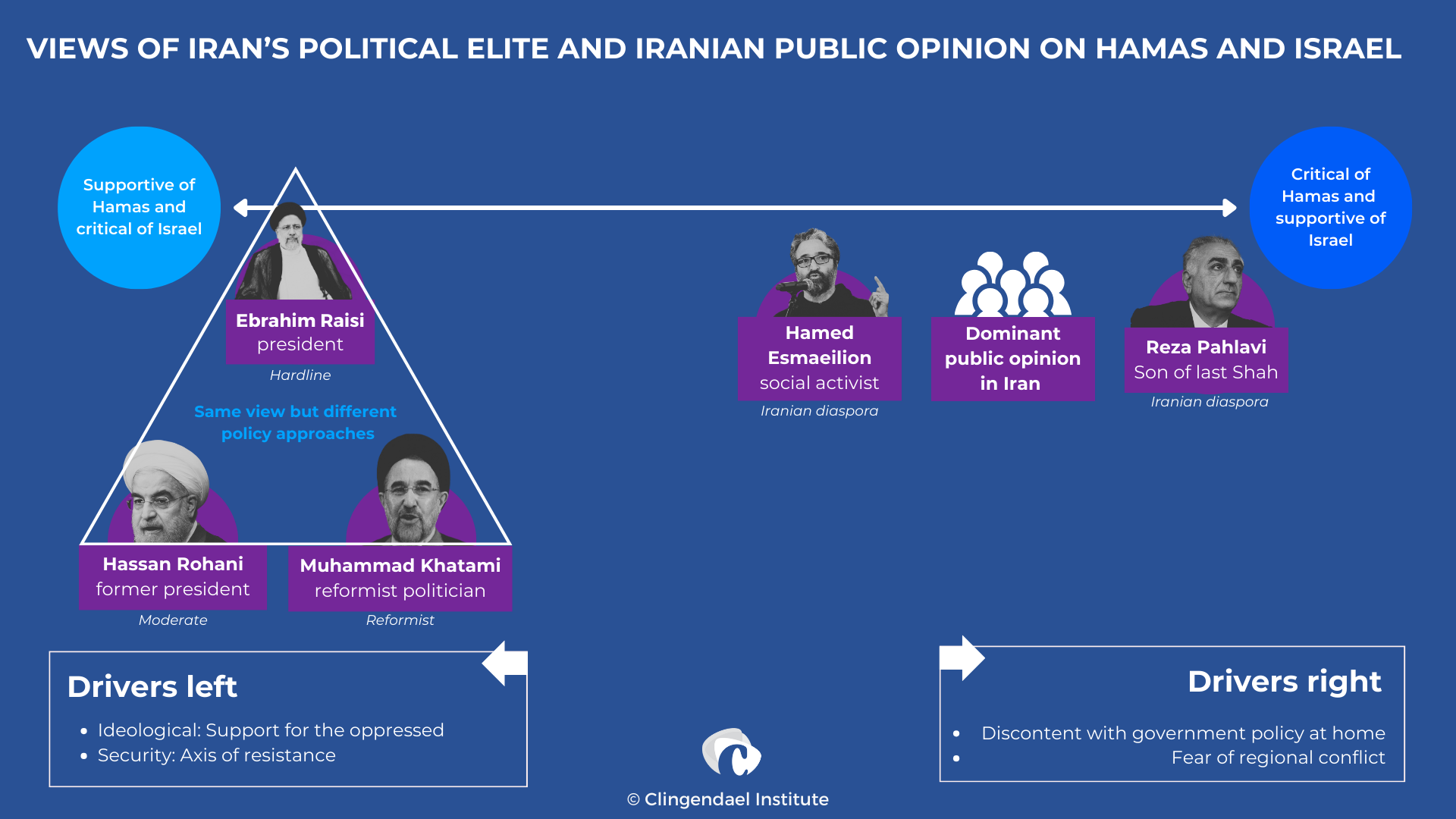

In the wake of the gruesome attack on Israel by Hamas on 7 October 2023, Iran’s senior officials, including Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei and President Ebrahim Raisi, promptly voiced their support for the movement while denying direct involvement. To date, no meaningful evidence of such involvement has surfaced, even though Hamas is undeniably part of Iran’s ‘axis of resistance’ and benefits from Iranian support via Hezbollah. Iran’s official stance against Israel and for Hamas is not limited to serving officials from the conservative/hardline camp. Reformist and moderate politicians by and large hold the same views. This rare consensus among Iran’s politically diverse elites underscores the deep-rooted nature of the Palestinian issue in Iranian politics, which transcends its usual factional divides. In consequence, Tehran has called on Islamic countries to take measures against Israel in response to its destruction of northern Gaza, like cutting diplomatic ties and imposing sanctions. Its proposal has not found any takers, however, since other Islamic nations have criticized Israel for its actions in Gaza, but stopped short of taking concrete measures against Tel Aviv.

The response of the Iranian public to the attack by Hamas and the subsequent war in Gaza stands in stark contrast with that of publics in other Islamic countries, however. In many Muslim nations, public condemnation of Israel outstrips governmental critiques by a wide margin – leading to extensive pro-Palestine protests – but this is much less the case in Iran. Notably, Iranian social media even feature pro-Israeli sentiments. This gap between the response of Iran’s political elites and its general population invites reflection on particular aspects of the country’s intra-elite and state-society dynamics, both of which are crucial to understand Iran’s transition.

7/10, the invasion of Gaza and intra-elite dynamics

Tehran’s stance on the Hamas attack on Israel and the ensuing invasion of Gaza has highlighted rare consensus among Iran’s various political factions, including hardliners, reformists and moderates. There are nevertheless differences in approach and rhetoric beneath the surface. Officially, the Islamic Republic maintains a consistent narrative in its portrayal of the invasion of Gaza through state media and government statements, namely one of unwavering support for the Palestinian cause. The government’s messaging emphasizes the need for resistance against Israeli aggression and Western imperialism, especially American. This portrayal aligns with Iran’s longstanding ideological commitment in support of Palestinian movements as cornerstone of Iranian foreign policy since 1979.

Within this general consensus, hardliners maintain the most radical stance in support of Hamas while reformist and moderate figures urge greater caution. Since reformist and moderate factions are traditionally more pragmatic in their approach to foreign policy, typically preferring diplomacy over confrontation (especially in matters involving the United States) their view on the Palestinian issue is no different. That’s why people like former Foreign Minister Mohammad Javad Zarif, former President Hassan Rouhani and former President Mohammad Khatami have emphasized the importance of the Palestinian cause, but also argued to restrict Iran's role to political support and avoid military entanglement. Reformist politician Mohsen Hashemi even cautioned against provoking Israel out of fear it might implicate Iran in its invasion of Gaza and shift the narrative to one about a broader regional war against Iran in a bid to garner wider international support.

Even though hardline media and ruling politicians criticized such calls for a measured approach – perceiving it as a deviation from core policy principles of the Islamic Republic – Tehran’s actual policy has nevertheless been rather cautious. This fact is not, however, openly acknowledged for reasons of public relations and intra-elite strife. Iran’s hardline ruling faction is reluctant to openly concede that a cautious policy might serve Iranian national interests better than its regular militant approach. The case offers a good example of how moderates, even though they are no longer in power, still influence major foreign policy decisions indirectly.

7/10, the invasion of Gaza and state-society relations in Iran

The attack of 7/10 and the invasion of Gaza triggered vastly different official and public responses in Iran. This divergence does not just reflect different opinions, it also illustrates a shift in how Iranian society engages with the government’s foreign policy. On social media, Iranians have expressed views that are critical of Hamas and sympathetic to Israel in a major departure of the government’s narrative. Public gatherings, such as football matches, have also become unexpected venues to express political dissent. Incidents at Tehran’s Azadi Stadium, where fans booed during a minute of silence for Gaza and protested against Palestinian flags, are indicative of this change in mood. This sentiment was already palpable in public chants during anti-government protests over the past years, during which demonstrators expressed frustration with the government allocating scarce resources to foreign policy rather than domestic problems. Such spontaneous (re-)actions contrast starkly with state-organized pro-Palestinian demonstrations that have had to deal with dwindling participation and enthusiasm. In the early years of the Islamic Republic, such protests drew large crowds of enthusiastic volunteers.

Drivers of this change in public opinion on Palestine include mounting domestic economic challenges in Iran that go unaddressed, a desire for more emphasis on national development and growing skepticism of the government’s foreign policy. However, it is born out of discontent with governmental policy rather than reflecting a genuine endorsement of Israeli positions and actions. The average Iranian’s understanding of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict is limited due to minimal direct contact and the dominance of either Iran’s state media or foreign-based opposition media, both of which tend to broadcast one-sided views. In essence, expressing support for Israel is a symbolic act of defiance for many Iranians against their own government. It reflects broader popular discontent with the Iranian government prioritizing Palestine (as well as Syria, Lebanon and Iraq) over pressing domestic concerns.

The Iranian diaspora has been influential in articulating and disseminating this critical popular narrative. Many of its members, such as Reza Pahlavi, have explicitly condemned Hamas and supported Israel. Others, like Hamed Esmaeilion, have taken a more balanced stance, which reflects diversity within the diaspora. In brief, many Iranians in the diaspora, just as in Iran itself, view support for Israel as another way to distance themselves from official Iranian policy.

The roots of official and public reactions

Experts and sociologists have traced the divergent reactions between state and society in Iran to 7/10 and the invasion of Gaza to several underlying factors. Ahmad Bokharaei, an Iranian sociologist, observes that the Iranian public perceives 7/10 and the invasion of Gaza as an extension of the proxy conflict between Iran and Israel. In turn, this triggers the memory of the eight-year-long Iran-Iraq war (1980-1988) with all its destruction and loss of life, which is seared into the national consciousness and deeply ingrained in Iranian society as a collective, not to mention its educational system. One long-term result of this war has been that Iranian society tends to favor diplomacy and negotiation over conflict and militancy, in contrast to its hardline elite that rules the country.

Similarly, prominent reformist figures like Abbas Abdi and Azar Mansouri have commented on the changing perceptions of the Iranian public towards the Palestinian issue. Abdi notes that ‘the decrease in public support for Palestine is not due to indifference toward injustice but stems from a shift in understanding the potential impact of this issue on Iran’ [Authors’ note: likely this is a reference to the economic cost of conflict with the US and Israel]. Abdi further argues that ‘this change is partly influenced by the government’s official positions, which have played a significant role in shaping public perception’ [Authors’ note: i.e. Tehran’s strengthening of the axis of resistance has made conflict more likely and the Iranian public has noticed]. Mansouri, on the other hand, highlights the difference in application of key principles of governance in Iran, particularly in its foreign policy. While the constitutional anchorage of ‘supporting the oppressed’ is firmly applied to Palestine, it is not to other conflicts such as for instance Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. She argues that the Iranian public’s lack of solidarity with Palestine is a result of such variations in implementation.

The government’s inability to persuade the public regarding the merits of its policies represents a final factor. The narrative that is broadcasted by state and state-affiliated media has failed to bridge the gap between public and political perceptions of the common good and public priorities. It cannot actually do so in a context of ruthless repression of protests that has highlighted major differences of focus between Iran’s political elites and public. This leads to a disconnect between official positions and public sentiment. Indeed, opposition to the Islamic Republic’s regional involvement is not new. During the 2009 Green Movement protests, slogans like “Neither Gaza, nor Lebanon, my life for Iran” already indicated growing public discontent with the government’s foreign policy priorities. This opposition has only grown over time.

In conclusion

Iranian political elites view and use the Palestinian issue to strengthen their narrative and practices of resistance against “Zionism and colonialism” across the region, which are ultimately based on Iran’s own foreign policy aspirations to be recognized as a regional power and to safeguard national security in the sense of regime survival. The Palestinian issue is also a convenient pressure point to keep Israel and the US distracted from other areas, such as Syria, Iraq and Yemen, not to mention Iran itself. However, hostile discourse creates expectations and practical support for Hamas creates new realities, both of which augment the risk of conflict escalation. Tehran’s rhetoric and actions also confirm the threat that Iran poses in the view of Israel, the US and a number of Arab countries on the Persian Gulf. Some have responded to this perceived threat with confrontation, others with rapprochement. It is because of such risks that parts of Iran’s political establishment urge caution in engaging on the Palestinian issue, especially with regards to a militant resistance group like Hamas that frequently targets non-combatants in violation of international humanitarian law.

In contrast, Iranian public sentiment is firmly opposed to ‘adventurism in Palestine’ as part of Iran’s broader regional security footprint. This represents less a lack of sympathy with ordinary Palestinians than it is a rejection of the priorities of successive Iranian governments, which have consistently ranked regional problems over domestic ones and allocated energy and resources accordingly.

To sum up, each group interprets and responds to the Palestinian issue through the lens of its own experiences, expectations and aspirations that are largely unrelated to Palestine. From the perspective of the Clingendael blog series ‘Iran in transition’, the broader point here is that the regional security policy of the Islamic Republic lacks popular support. This has two main consequences. First, should a larger regional conflict erupt that results in widespread death and destruction, its unpopularity with the Iranian public will likely act as a brake on how long it can be maintained at high levels of intensity. Second, the Islamic Republic’s adversaries are likely to use the contrast between the foreign policy priorities of the regime and the domestic economic priorities of its population as an important element in their strategic communication that seeks to undermine what remains of the regime’s popular support and, indirectly, to stoke discontent.